Feb 17 2026

/

Why Most RWE Fails Payer Scrutiny (and What Actually Passes)

Real-world evidence is no longer optional in market access discussions. Payers expect it. HTA bodies ask for it. Internal teams invest heavily in generating it. And yet, a quiet reality persists: most RWE never meaningfully influences payer decisions.

It isn’t rejected outright. It’s acknowledged, parked, and ultimately sidelined.

The issue isn’t skepticism toward real-world data. It’s relevant. Too much RWE is built to demonstrate analytical effort rather than to reduce payer uncertainty at the moment a decision is made.

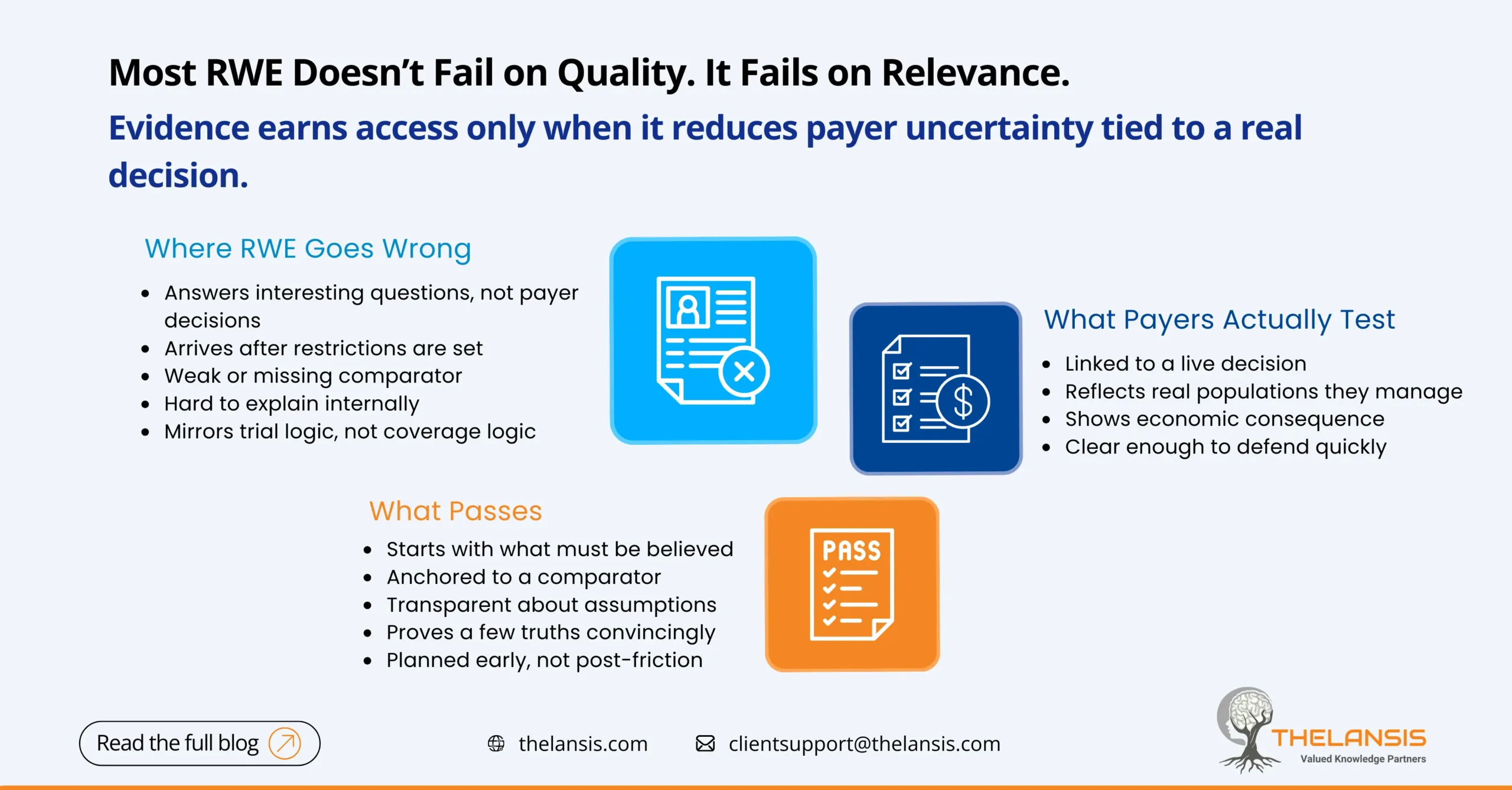

Where RWE Goes Wrong

The most common failure is simple: RWE answers the wrong question. Many studies focus on describing disease burden, mapping treatment pathways, or validating findings from clinical trials. While useful context, these insights rarely help a payer decide whether to reimburse, restrict, reassess, or expand coverage. Payers are not asking whether a therapy works in theory. They are asking whether it will change outcomes they pay for, in populations they manage, at a cost they can defend.

Another issue is timing. RWE is often commissioned after launch, once access friction has already appeared. At that point, pricing anchors are set, restrictions are in place, and the payer’s risk posture is locked in. Evidence that arrives late is treated as retrospective justification rather than decision support.

Comparator weakness is another common pitfall. Single-arm RWE without a credible benchmark struggles to survive scrutiny. If the alternative care pathway isn’t explicit, realistic, and transparent, payers have no reference point to judge value. Without a believable counterfactual, even clean data loses influence.

Finally, many RWE studies mirror clinical trial logic instead of payer logic. They prioritize statistical sophistication over interpretability. Payers rarely need methodological perfection; they need clarity that they can explain internally without months of follow-up.

What Payers Actually Evaluate

Although rarely stated explicitly, payer scrutiny tends to focus on a few consistent principles.

First is decision alignment. Evidence that passes scrutiny is tied to a live or upcoming decision: coverage scope, step edits, population expansion, or re-assessment. If the RWE cannot be clearly linked to a concrete action, it floats.

Second is population specificity. Broad averages matter less than evidence that reflects real eligibility filters, disease severity mix, comorbidities, and prior treatment patterns. Payers want to see themselves in the data.

Third is the economic consequence. Clinical outcomes matter, but outcomes linked to avoidable hospitalizations, reduced resource use, or downstream cost offsets are what move coverage discussions forward.

What Actually Passes Payer Scrutiny

Successful RWE is designed backward from the payer question, not forward from available data. It starts by asking what level of confidence is required for a specific decision and what uncertainty needs to be reduced.

Passing RWE is anchored to a comparator, even if imperfect, and transparent about its assumptions. It does not try to prove everything. It proves one or two payer-relevant truths well.

Critically, it is integrated early. RWE that shapes access is often planned before Phase III concludes, not as a corrective measure after launch disappointment.

The Real Shift Required

The future of RWE is not bigger datasets or longer reports. It has a sharper intent.

Payers do not reward effort. They reward usefulness. When RWE is built to reduce decision risk, rather than to showcase analytical capability, it stops being a supportive appendix and starts becoming part of the access strategy itself.

If real-world evidence isn’t changing what a payer does next, it isn’t failing because payers don’t trust it. It’s failing because it was never built for the decision in the first place.