Nov 14 2025

/

The Forgotten Power of the TPP: Why Many Biopharma Projects Fail Without It

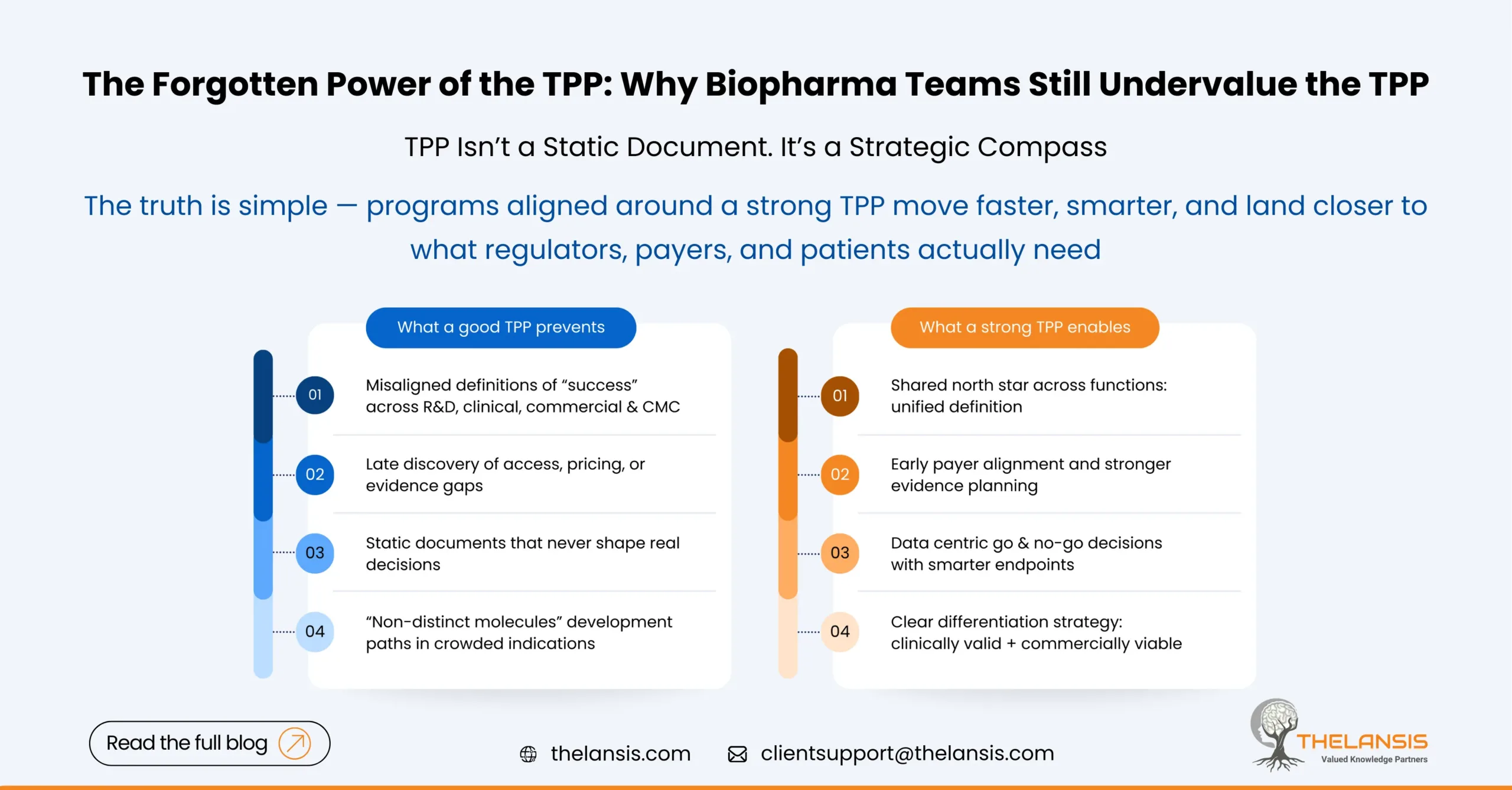

In the fast‐moving world of biopharma innovation, it’s easy to get excited by the science – the novel target, the breakthrough molecule, the cutting-edge modality. But amid that excitement, one strategic document often gets overlooked or relegated to a checkbox: the Target Product Profile (TPP). Too often, teams pour years of effort and resources into a promising molecule, only to realize late in the process that what they’ve built isn’t quite what the regulators, payers, or patients actually needed. That’s a missed opportunity, because when used right, a well-crafted TPP doesn’t just guide development. It connects science with strategy, aligning every function — from R&D and regulatory to commercial and manufacturing — around one clear vision of what success should look like.

What Exactly Is a TPP?

At its core, a Target Product Profile (TPP) is a living blueprint that defines the intended attributes of a future therapeutic product. It outlines key elements like indication, patient population, efficacy expectations, safety targets, route of administration, dosing frequency, and even commercial positioning.

Regulators like the FDA and EMA encourage companies to use TPPs early in development to align on the eventual label claims. But beyond compliance, it’s a critical tool that ensures the entire organization is building toward a shared end goal rather than working in silos.

Why Projects Fail Without a Strong TPP?

1. No Shared Definition of “Winning”

Without a clear TPP, different functions define success differently. Clinical teams chase endpoints that may not align with what payers consider meaningful. For instance, manufacturing may scale for a product design that’s later revised, or marketing teams might prepare for an indication that doesn’t get approved.

A TPP ensures everyone’s working toward the same outcome, it defines not just the “what” but the “why.”

2. Late Realization of Commercial Gaps

A common pattern we see: a molecule shows great clinical efficacy but fails to secure market traction post-launch. Take Zynteglo, Bluebird Bio’s one-time gene therapy for transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia. The therapy achieved high transfusion-independence rates and even gained EMA approval in 2019. Yet, payer bodies like NICE rejected it due to its staggering price tag (around £1.45 million per treatment) and limited long-term data.

Clinically, it succeeded. Commercially, it stumbled. Why? Because the value proposition and reimbursement case were not built in parallel with the science, something a robust TPP process would have forced into early focus.

3. Overly Aspirational or Static Documents

Many companies treat the TPP as a checkbox exercise or as a marketing wish list. It becomes an aspirational document rather than a decision-making tool. A good TPP evolves — it starts with hypotheses, gets refined with data, and is continuously stress-tested against competitors, regulators, and payers.

4. Poor Cross-Functional Ownership

When the TPP sits only with clinical or regulatory teams, it loses strategic weight. The most successful organizations make it a joint responsibility across R&D, commercial, market access, and CMC. That shared ownership transforms the TPP from a file into a strategic alignment mechanism.

A Lesson from Oncology: Clarity Beats Complexity

In oncology, the TPP mostly determines which programs get prioritized. For instance, when Merck advanced pembrolizumab (Keytruda), their TPP was remarkably clear focusing on broad tumor coverage, immune-checkpoint inhibition, and biomarker-driven differentiation. Every study design, partnership, and indication expansion traced back to that north star.

Compare that with smaller oncology biotechs that enter crowded indications without defining their differentiation early. Many end up with “me-too” molecules — clinically valid but commercially invisible.

TPP as a Strategic Compass — Not a Static Document

In consulting, we often encourage clients to treat the TPP like a control tower dashboard. It should constantly answer key questions:

- Are we still on track to meet our target indication?

- Has the standard of care evolved?

- Do payers still value the endpoints we’re pursuing?

- Are manufacturing and logistics aligned with the intended market?

When the answers start diverging, the TPP is the first place you revisit.

Building a Strong TPP: Best Practices from the Field

- Start Early – Don’t wait until Phase 2. Draft your first TPP once a viable lead is identified.

- Involve Everyone – Regulatory, clinical, market access, CMC, commercial — all must have a voice.

- Define “Minimum” vs “Ideal” Targets – Establish what’s essential for success and what’s aspirational.

- Integrate Market Access Early – Payers’ perspectives are as critical as regulators’.

- Update Regularly – Treat it as a dynamic tool; update as data and the external environment evolve.

- Link to Decision Gates – Use it to drive go/no-go decisions, not just reporting.

- Embed in Dashboards – Just like supply chain KPIs, track progress against your TPP metrics regularly.

Closing Thoughts:

Drug development will always carry uncertainty, but strategic misalignment is preventable. The TPP sits at the intersection of vision and execution, ensuring that every dollar, data point, and decision moves toward a shared goal.

It doesn’t require fancy analytics or massive budgets, it just requires disciplined, cross-functional collaboration and a clear definition of what “good” truly looks like. The TPP may not grab headlines, but it quietly determines which molecules reach patients and which never make it past the boardroom. Ignoring it isn’t just a missed opportunity which a few companies can afford.